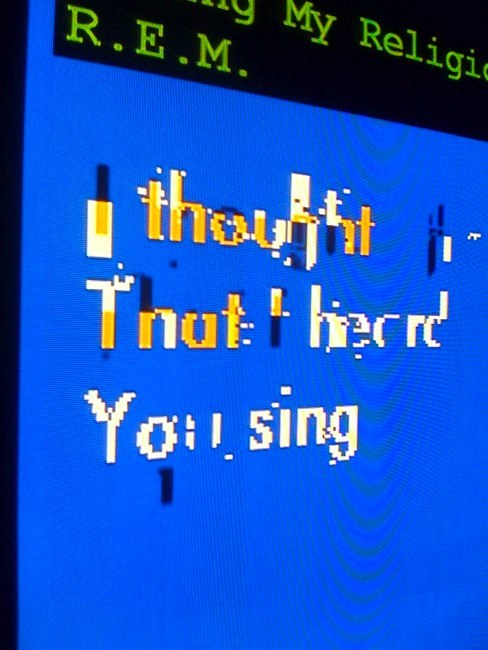

GLTI.CH Karaoke

GLTI.CH Karaoke is a collaborative mess between Kyougn Kmi and Dnaiel Roruke

Caught between a glide and a slip, the glitch exposes the course of accidents, of temporary lyrical disjoints and the technical out-of-syncs. From the Japanese for ‘empty’ and the English ‘orchestra’ Kara-oke is a global portmanteau, errored in the translation between screens and earworms. GLTI.CH Karaoke establishes its own time-codes as webcam data jolts and audio streams jostle from server to internet server. GLTI.CH Karaoke duets with global hit parades, clashing together in mutual mis-syncs, each relative to its other. With a fondness for compressed pixels and midi programmed synthetics, GLTI.CH Karaoke is a moving, not a movement. A rapid infection spreading like an earworm across nations and networks, GLTI.CH Karaoke asks humans to err: to seek out the Gremlin and live with it.

Errors in Things and “The Friendly Medium”

What is it about a particular media that makes it successful? Drawing a mini history from printing-press smudges to digital compression artefacts this lecture considers the value of error, chance and adaptation in contemporary media. Biological evolution unfolds through error, noise and mistake. Perhaps if we want to maximise the potential of media, of digital text and compressed file formats, we first need to determine their inherent redundancy. Or, more profoundly, to devise ways to maximise or even increase that redundancy.

This presentation was designed and delivered as part of Coventry University, Media and Communication Department’s ‘Open Media‘ lecture series. Browse the Open-Media /stream for related material.

UPDATE: The audio recording and powerpoint presentation (should) work in harmony.

Listen/watch/download here:

[audio:http://machinemachine.net/noise/open_media_Lecture_Daniel_Rourke_feb_2011.mp3|titles=Errors in Things and “The Friendly Medium”]Browse the Open-Media /stream for related material

[scribd id=48954914 key=key-19gpngehvexs2igqlaca mode=slideshow]

Many thanks to Janneke Adema for inviting me to present this talk and for all her hard work with the series and podcast.

On (Text and) Exaptation

(This post was written as a kind of ‘prequel’ to a previous essay, Rancière’s Ignoramus)

‘Text’ originates from the Latin word texere, to weave. A material craft enabled by a human ingenuity for loops, knots and pattern. Whereas a single thread may collapse under its own weight, looped and intertwined threads originate their strength and texture as a network. The textile speaks of repetition and multiplicity, yet it is only once we back away from the tapestry that the larger picture comes into focus.

At an industrial scale textile looms expanded beyond the frame of their human operators. Reducing a textile design to a system of coded instructions, the complex web of a decorative rug could be fixed into the gears and pulleys that drove the clattering apparatus. In later machines long reels of card, punched through with holes, told a machine how, or what, to weave. Not only could carpets and textiles themselves be repeated, with less chance of error, but the punch-cards that ordered them were now equally capable of being mass-produced for a homogenous market. From one industrial loom an infinite number of textile variations could be derived. All one needed to do was feed more punch-card into the greedy, demanding reels of the automated system.

The material origins of film may also have been inspired by weaving. Transparent reels of celluloid were pulled through mechanisms resembling the steam-driven contraptions of the industrial revolution. The holes running down its edges delimit a reel’s flow. Just as the circular motion of a mechanical loom is translated into a network of threads, so the material specificity of the film-stock and projector weave the illusion of cinematic time. Some of the more archaic, out-moded types of film are known to shrink slightly as they decay, affording us – the viewer – a juddering, inconsistent vision of the world captured in the early 20th century.

In 1936, the year that Alan Turing wrote his iconic paper “On Computable Numbers”, a German engineer by the name of Konrad Zuse built the first working digital computer. Like its industrial predecessors, Zuse’s computer was designed to function via a series of holes encoding its program. Born as much out of convenience as financial necessity, Zuse punched his programs directly into discarded reels of 35mm film-stock. Fused together by the technologies of weaving and cinema, Zuse’s digital computer announced the birth of an entirely new mode of textuality. As Lev Manovich suggests:

In 1936, the year that Alan Turing wrote his iconic paper “On Computable Numbers”, a German engineer by the name of Konrad Zuse built the first working digital computer. Like its industrial predecessors, Zuse’s computer was designed to function via a series of holes encoding its program. Born as much out of convenience as financial necessity, Zuse punched his programs directly into discarded reels of 35mm film-stock. Fused together by the technologies of weaving and cinema, Zuse’s digital computer announced the birth of an entirely new mode of textuality. As Lev Manovich suggests:

“The pretence of modern media to create simulations of sensible reality is… cancelled; media are reduced to their original condition as information carrier, nothing less, nothing more… The iconic code of cinema is discarded in favour of the more efficient binary one. Cinema becomes a slave to the computer.”

Rather than Manovich’s ‘slave’ / ‘master’ relationship, I want to suggest a kind of lateral pollination of media traits. As technologies develop, specificities from one media are co-opted by another. Reverting to biological metaphor, we see genetic traits jumping between media species.

From a recent essay by Svetlana Boym, The Off-Modern Mirror:

“Exaptation is described in biology as an example of “lateral adaptation,” which consists in a cooption of a feature for its present role from some other origin… Exaptation is not the opposite of adaptation; neither is it merely an accident, a human error or lack of scientific data that would in the end support the concept of adaptation. Exaptation questions the very process of assigning meaning and function in hindsight, the process of assigning the prefix “post” and thus containing a complex phenomenon within the grid of familiar interpretation.”

Media history is littered with exaptations. Features specific to certain media are exapted – co-opted – as matters of convenience, technical necessity or even aesthetics. Fashion has a role to play also, for instance, many of the early models of mobile phone sported huge, extendible aerials which the manufacturers now admit had no impact whatsoever on the workings of the technology.

Lev Manovich’s suggestion is that as the computer has grown in its capacities, able to re-present all other forms of media on a single computer apparatus, the material traits that define a media have been co-opted by the computer at the level of software and interface. A strip of celluloid has a definite weight, chemistry and shelf-life – a material history with origins in the mechanisms of the loom. Once we encode the movie into the binary workings of a digital computer, each media-specific – material – trait can be reduced to an informational equivalent. If I want to increase the frames per second of a celluloid film I have to physically wind the reel faster. For the computer encoded, digital equivalent, a code that re-presents each frame can be introduced via my desktop video editing software. Computer code determines the content as king.

Lev Manovich’s suggestion is that as the computer has grown in its capacities, able to re-present all other forms of media on a single computer apparatus, the material traits that define a media have been co-opted by the computer at the level of software and interface. A strip of celluloid has a definite weight, chemistry and shelf-life – a material history with origins in the mechanisms of the loom. Once we encode the movie into the binary workings of a digital computer, each media-specific – material – trait can be reduced to an informational equivalent. If I want to increase the frames per second of a celluloid film I have to physically wind the reel faster. For the computer encoded, digital equivalent, a code that re-presents each frame can be introduced via my desktop video editing software. Computer code determines the content as king.

In the 1960s and 70s Roland Barthes named ‘The Text’ as a network of production and exchange. Whereas ‘the work’ was concrete, final – analogous to a material – ‘the text’ was more like a flow, a field or event – open ended. Perhaps even infinite.

In, From Work to Text, Barthes wrote:

“The metaphor of the Text is that of the network…”

This semiotic approach to discourse, by initiating the move from print culture to ‘text’ culture, also helped lay the ground for a contemporary politics of content-driven media.

Skipping backwards through From Work to Text, we find this statement:

“The text must not be understood as a computable object. It would be futile to attempt a material separation of works from texts.”

I am struck here by Barthes’ use of the phrase ‘computable object’, as well as his attention to the ‘material’. Katherine Hayles in her essay, Text is Flat, Code is Deep, teases out the statement for us:

“computable” here mean[s] to be limited, finite, bound, able to be reckoned. Written twenty years before the advent of the microcomputer, his essay stands in the ironic position of anticipating what it cannot anticipate. It calls for a movement away from works to texts, a movement so successful that the ubiquitous “text” has all but driven out the media-specific term book.

Hayles notes that the ‘ubiquity’ of Barthes’ term ‘Text’ allowed – in its wake – an erasure of media-specific terms, such as ‘book’. In moving from, The Work to The Text, we move not just between different politics of exchange and dissemination, we also move between different forms and materialities of mediation. To echo (and subvert) the words of Marshall Mcluhan, not only is The Medium the Message, The Message is also the Medium.

…media are only a subspecies of communications which includes all forms of communication. For example, at first people did not call the internet a medium, but now it has clearly become one… We can no longer understand any medium without language and interaction – without multimodal processing… We are now clearly moving towards an integration of all kinds of media and communications, which are deeply interconnected.

Extract from a 2005 interview with Manuel Castells, Global Media and Communication Journal

(This post was written as a kind of ‘prequel’ to a previous essay, Rancière’s Ignoramus)

The Clock

Language is not what it is because it has meaning… It is a fragmented nature, divided against itself and deprived of its original transparency by admixture; it is a secret that carries within itself, though near the surface, the decipherable signs of what it is trying to say. It is at the same time a buried revelation and a revelation that is gradually being restored to ever greater clarity.

Michel Foucault, The Order of Things

Every Thing has to end, but not so its fragments. Energy flows amongst systems. It constitutes as it destroys, but never does energy itself dissipate completely. All flow is transformation. Re-figuration is the enemy of entropy.

Christian Marclay’s new work, The Clock, currently on show at The White Cube in London, constitutes a new system from old fragments. Comprised of 24 hours of film segments, Marclay’s work offers the viewer a real-time database of clock faces captured by Marclay and forced into the cinematic paradigm. What fascinates most about this work (and at this stage, I must admit, I have not seen it) is its explicit totality: Marclay’s film effectively closes the image of time within the loop of a 24 hour cinematic. The database of clock faces ebbs forever forwards, closed into itself as loop. This is not only our shared perception of time, it is also a perception without which the art of cinema may never have emerged.

Christian Marclay’s new work, The Clock, currently on show at The White Cube in London, constitutes a new system from old fragments. Comprised of 24 hours of film segments, Marclay’s work offers the viewer a real-time database of clock faces captured by Marclay and forced into the cinematic paradigm. What fascinates most about this work (and at this stage, I must admit, I have not seen it) is its explicit totality: Marclay’s film effectively closes the image of time within the loop of a 24 hour cinematic. The database of clock faces ebbs forever forwards, closed into itself as loop. This is not only our shared perception of time, it is also a perception without which the art of cinema may never have emerged.

Put another way, Marclay’s work exposes the rigidity of not only the cinematic (a reel spins in only two directions) but also the conception of time (arguably a ‘Western’ one) that figures it. But – and this ‘but’ should be writ larger than my database of fonts allows me – Marclay’s work is a work made manageable in its making by a technology seemingly free of forward/backward limitations. For writer and theorist Lev Manovich the computer/digital database plays a fundamental role in transforming the hidden data set (thousands of individual film segments of clocks/time) and the material expression (the 24 hour long film) into the each of its other:

Literary and cinematic narratives work in the same way. Particular words, sentences, shots, scenes which make up a narrative have a material existence; other elements which form an imaginary world of an author or a particular literary or cinematic style and which could have appeared instead exist only virtually. Put differently, the database of choices from which narrative is constructed (the paradigm) is implicit; while the actual narrative (the syntagm) is explicit.

New media reverses this relationship. Database (the paradigm) is given material existence, while narrative (the syntagm) is de-materialised. Paradigm is privileged, syntagm is downplayed. Paradigm is real, syntagm is virtual.

Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media

Marclay’s gathering of clock footage only ever had one, obsessively realised, end point. The point when every second of the Earthly day (morning/noon/night) was figured, classed and catalogued by the totalising database. Here we find a metaphor impossible to mistake: that of a digital present, forever engaged in the cataloging of its own archaeology.

Cuttings, fragments. Old medias torn and compressed into digital instances and made to float between databases. This is the status of art today. It is not a new approach Marclay wields in his work, but in its totality (or its illusion of totality) The Clock must be one of the most successful attempts to figure the contemporary I have yet come across.

And Another ‘Thing’ : Sci-Fi Truths and Nature’s Errors

In my last 3quarksdaily article I considered the ability of science-fiction – and the impossible objects it contains – to highlight the gap between us and ‘The Thing Itself’ (the fundamental reality underlying all phenomena). In this follow-up I ask whether the way these fictional ‘Things’ determine their continued existence – by copying, cloning or […]

‘The Thing Itself’ : A Sci-Fi Archaeology

Mid-way through H.G.Wells’ The Time Machine, the protagonist stumbles into a sprawling abandoned museum. Sweeping the dust off ancient relics he ponders his machine’s ability to hasten their decay. It is at this point that The Time Traveller has an astounding revelation. The museum is filled with artefacts not from his past, but from his […]

Rancière’s Ignoramus

Jacques Rancière prepares for us a parable. A student who is illiterate, after living a fulfilled life without text, one day decides to teach herself to read. Luckily she knows a single poem by heart and procures a copy of that poem, presumably from a trusted source, by which to work. By comparing her knowledge, sign by sign, word by word, with the poem she can, Rancière believes, finally piece together a foundational understanding of her language:

“From this ignoramus, spelling out signs, to the scientist who constructs hypotheses, the same intelligence is always at work – an intelligence that translates signs into other signs and proceeds by comparisons and illustrations in order to communicate its intellectual adventures and understand what another intelligence is endeavoring to communicate to it.

This poetic labour of translation is at the heart of all learning.”

The Emancipated Spectator (2008)

What interests me in Rancière’s example is not so much the act of translation as the possibility of mis-translation. Taken in light of The Ignorant Schoolmaster we can assume that Rancière is aware of the wide gap that exists between knowing something and knowing enough about something for it to be valuable. But what distinction can we uncover between the ‘true’ and the ‘false’, hell, even between the ‘true’ and ‘almost true’? How does one calculate the value of what is effectively a mistake?

What interests me in Rancière’s example is not so much the act of translation as the possibility of mis-translation. Taken in light of The Ignorant Schoolmaster we can assume that Rancière is aware of the wide gap that exists between knowing something and knowing enough about something for it to be valuable. But what distinction can we uncover between the ‘true’ and the ‘false’, hell, even between the ‘true’ and ‘almost true’? How does one calculate the value of what is effectively a mistake?

Error appears to be a crucial component of Rancière’s position. In a sense, Rancière is positing a world that has from first principles always uncovered itself through a kind of decoding. A world in which subjects “translate signs into other signs and proceed by comparison and illustration”. Now forgive me for side-stepping a little here, but doesn’t that sound an awful lot like biological development? Here’s a paragraph from Richard Dawkins (worth his salt as long as he is talking about biology):

“Think about the two qualities that a virus, or any sort of parasitic replicator, demands of a friendly medium, the two qualities that make cellular machinery so friendly towards parasitic DNA, and that make computers so friendly towards computer viruses. These qualities are, firstly, a readiness to replicate information accurately, perhaps with some mistakes that are subsequently reproduced accurately; and, secondly, a readiness to obey instructions encoded in the information so replicated.”

Viruses of the Mind (1993)

Hidden amongst Dawkins’ words, I believe, we find an interesting answer to the problem of mis-translation I pose above. A mistake is useless if accuracy is your aim, but what if your aim is merely to learn something? To enrich and expand the connections that exist between your systems of knowledge. As Dawkins alludes to above, it is beneficial for life that errors do exist and are propagated by biological systems. Too many copying errors and all biological processes would be cancerous, mutating towards oblivion. Too much error management (what in information theory would be metered by a coded ‘redundancy‘) and biological change, and thus evolution, could never occur.

Simply put, exchange within and between systems is almost valueless unless change, and thus error, is possible within the system. At the scale Rancière exposes for us there are two types of value: firstly, the value of repeating the message (the poem) and secondly, the value of making an error and thus producing entirely new knowledge. In information theory the value of a message is calculated by the amount of work saved on the part of the receiver. That is, if the receiver were to attempt to create that exact message, entirely from scratch.

In his influential essay, Encoding, Decoding (1980), Stuart Hall maps a four-stage theory of “linked but distinctive moments” in the circuit of communication:

- production

- circulation

- use (consumption)

- reproduction

John Corner further elaborates on these definitions:

- the moment of encoding: ‘the institutional practices and organizational conditions and practices of production’;

- the moment of the text: ‘the… symbolic construction, arrangement and perhaps performance… The form and content of what is published or broadcast’; and

- the moment of decoding: ‘the moment of reception [or] consumption… by… the reader/hearer/viewer’ which is regarded by most theorists as ‘closer to a form of “construction”‘ than to ‘the passivity… suggested by the term “reception”‘

(source)

At each ‘moment’ a new set of limits and possibilities arises. This means that the way a message is coded/decoded is not the only controlling factor in its reception. The intended message I produce, for instance, could be circulated against those intentions, or consumed in a way I never imagined it would be. What’s more, at each stage there emerges the possibility for the message to be replicated incorrectly, or, even more profoundly, for a completely different component of the message to be taken as its defining principle.

Let’s say I write a letter, intending to send it to my newly literate, ignoramus friend. The letter contains a recipe for a cake I have recently baked. For some reason my letter is intercepted by the CIA,who are convinced that the recipe is a cleverly coded message for building a bomb. At this stage in the communication cycle the possibility for mis-translation to occur is high. Stuart Hall would claim is that this shows how messages are determined by the social and institutional power-relations via which they are encoded and then made to circulate. Any cake recipe can be a bomb recipe if pushed into the ‘correct’ relationships. Every ignoramus, if they have the right teacher, can develop knowledge that effectively lies beyond the teacher’s.

What it is crucial to understand is that work is done at each “moment” of the message. As John Corner states, decoding is constructive: the CIA make the message just as readily as I did when I wrote and sent it.

These examples are crude, no doubt, but they set up a way to think about exchange (communication and information) through its relationships, rather than through its mediums and methods. The problem here that requires further examination is thus:

What is ‘value’ and how does one define it within a relational model of exchange?

Like biological evolution, information theory is devoid of intentionality. Life prospers in error, in noise and mistakes. Perhaps, as I am coming to believe, if we want to maximise the potential of art, of writing and other systems of exchange, we first need to determine their inherent redundancy. Or, more profoundly, to devise ways to maximise or even increase that redundancy. To determine art’s redundancy, and then, like Rancière’s ignoramus, for new knowledge to emerge through mis-translation and mis-relation.